This week, Google announced that it’s shutting down Reader. This is the first of Google’s “sunsets” that hits me personally – Reader has been a crucial part of my internet use for the better part of a decade. I happen to think, like Marco Arment, that in the long run the loss of Google Reader will probably be good for innovation in RSS readers and for RSS in general. Google’s hamstrung app has been just good enough for people like me, but non-approachable for non-geeks. A year from now, I’m hoping that there’ll be many more quality players. So, in the long run, I’m reasonably optimistic.

More immediately, though, a couple of causes for concern:

-

Finding an alternative to Reader. My RSS reading habits are too ingrained for me to abandon them, even for a short time. More than that: following RSS feeds is beyond mere habit, but is check on my intellectual honesty. I follow many blogs whose authors I frequently disagree with, or even dislike. (Contrast this with Twitter, where I’m pretty fickle about whom I follow, and how many tweets/links I pay attention to.) So RSS is, for me, a partial antidote to the echo chamber tendency. That means that I’ve got to find a new app, and migrate over, and I’ve got to do it quickly.

There have been a number of posts over the last couple days listing Reader alternatives. A number of them are cloud/service based, and for practical reasons (such as, um, Google Reader) as well as philosophical reasons (see below), I’m only considering alternative tools that I can run either locally or on my own server. A couple that spring to mind:

- Fever. I’m interested in this one because (a) the screenshots make it look nice, and (b) it comes highly recommended by people I respect, like D’Arcy Norman. I like that it’s self-hosted. I don’t like the fact that its sustainability model is to charge for downloads. It’s not that I don’t think the author shouldn’t be paid – I would be happy to pay $30 or $300 for a great RSS reader app. It’s that the success of the single-developer model is contingent on the willingness of that developer to keep working on the project (paid or otherwise). I’m far more comfortable with software that is community developed under a free license, ideally using a set of technologies that would allow me to modify or even adopt the project if the main devs were to abandon it.

- Tiny Tiny RSS. tt-rss also comes recommended by someone I respect (Mika Epstein, in this case). And it’s community-developed, which I like. It doesn’t look as pretty as Fever, but aesthetics are about fourth or fifth on my list of requirements.

- PressForward. As Aram describes, the PF team (of which I’m pleased to be a member) is working on a WordPress-based tool that, among other things, does RSS aggregation and provides some feed-reading capabilities. PressForward is really designed for a different kind of use case – where groups of editors work together to pare down large amounts of feed data into smaller publications – but it could be finagled to be a simple feed reader. Mobile support is a particular pain point, as 50% or more of my RSS intake is done on my phone, and PF has nothing in place to make this possible at the present time. So, PressForward may not be quite ready for primetime, but I do think that it has promise.

-

Get the hell off of Google. We all know that Google is a company with shareholders and profit goals to meet. Yet we often act like Google is some sort of ambient benevolent force on the web. Since I started Project Reclaim, I’ve been working on extricating myself and my data from the clutches of Google (among other corporate entities). Reader’s demise is a wake-up call that the time for dilly-dallying is over.

For my own part, I still use a few Google services besides Reader:

- Gmail. I don’t use Gmail primarily anymore, though many people do still email me at my gmail.com address, so obviously I have it open and I check it frequently.

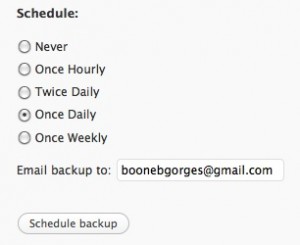

- Picasa. I use the Picasa desktop app on OSX to export photos from my cameras and organize/tag them. I also use Picasa Web Albums as one of my many photo backup services. (Seriously – I back up my photos to no fewer than six different local and cloud services. Nothing is more important or irreplaceable than my family photos.)

- Drive/Docs. Aside from the occasional one-off collaborations, I use Drive to maintain a number of spreadsheets and other documents that I share with members of my family, etc.

- Calendar. I’m not a heavy calendar user, but when I do use a calendar, I like Google because of its integration with my Android phone.

- Chromium. Not Chrome, but still largely Google-reliant, Chromium is not my main browser, but I use it daily for doing various sorts of development testing.

- Android. This is maybe the one that steams me the most, because at the moment there are no truly free alternatives. (Firefox OS, please hurry up.)

In some of these cases, there are easy ways to get off of the Google services. In others, it’ll be a challenge to find alternatives that provide the same functionality. In any case, the Reader slaughter is a harsh reminder that Project Reclaim has stagnated too long with respect to Google services.

More than myself, I’m worried about others – those who aren’t as technically inclined as I am, or those who simply don’t care as much as I do. Google’s made it pretty clear (as is their right, I guess) that they’re not an ambient benevolence. Those who rely on Google then, especially for critical services like email, should take this warning very seriously. Please consider carefully what you’re doing when you make yourself wholly dependent on the whim’s of Google’s product managers, and consider options that are either free-as-in-speech, or services that you pay for in a traditional way.