I was honored to present the keynote address at this year’s WordCamp New York. Below is a rough copy of the text with some of the slides interspersed. (“Rough” means cobbled together from my notes, and minus most of the ***hilarious*** jokes. I guess you had to be there.) The video will be up on wordpress.tv within a few weeks.

===

The title of my talk today is “Free Software, Free Labor, and the Freelancer”. I’ve been asked to give this particular talk because I’m a freelancer who devotes large amounts of free labor to free software projects. The gist of my argument is going to be that freelancers can and should contribute more than they do, and I’m going to make this argument in a way that is sensitive to the economic concerns that are particular to freelancers and small business owners. I’m a developer, so most of what I’ll say will be specific to people who write code; there’s a lot to be said about the imbalances between coders and non-coders in a project like WordPress, but that’s a subject for another talk.

I’d like to start off by asking what it means when we say that WordPress is “free”. Many of the people in this room could rattle off, in their sleep, the two senses of the English word “free” when it comes to free software. What’s less often noticed is how these two senses can be at odds with each other. Let’s spell that out a bit.

The first sense in which WordPress is free is “free as in free beer”. When I invite you to my dorm room for a free Blatz, what I mean is that I’m not going to ask you for the 50 cents to recoup my initial outlay. “Free beer” is beer that you don’t have to pay for. And WordPress itself is free in this sense, because, in contrast to software like, say, Microsoft Windows, you don’t have to pay anyone to download or use the software.

But this is, of course, a secondary sense of “free”. When we think of WordPress as free software, what we really mean is “free as in freedom”. In technical terms, this means that WordPress is released under a free software license – in our case, the GNU General Public License, or GPL. The terms of the GPL can be summarized by the four essential freedoms that they guarantee to users of the software: (0) the freedom to use the software for any purpose; (1) the freedom to study and modify the software as they’d wish (this is the “open source” part); (2) the freedom to redistribute the original software; and (3) the freedom to distribute any modifications to the software. The GPL guarantees that users have these freedoms with respect to WordPress, and this is the primary sense in which WordPress is “free”.

The point I want to make at the moment is that these two senses of the word “free” are, in some sense, in conflict with each other with respect to software like WordPress. The root of the conflict is that building software – especially good software – is hard: programming is hard, design is hard, documentation is hard, support is hard, community building is hard. The fact that these things are hard mean that it takes a lot of people and a lot of time to build software. And this means, in turn, that it costs a lot of money to build software.

The traditional strategy for addressing this problem is to make your software proprietary. If you charge a couple hundred million people $100 each to use your software, you’ll have a few billion dollars that you can use to pay an army of programmers, designers, etc to build and maintain that software. But, prima facie, it’s tricky to keep this system up and running – the money only keeps rolling in if people are forced to pay in order to use the software, but software is by its very nature the kind of thing that can be infinitely copied and sent around the internet. The creators of proprietary software combat this problem by locking down their tools in a couple of ways. They lock it down in a legal sense, by requiring you to agree to End User License Agreements and other mumbo jumbo before using. They lock it down in a technical sense, through the use of license keys, DRM, and the like. And they lock it down through propaganda, such as the convention of using the word “piracy” to describe something that, in fact, is quite different from stabbing someone with a cutlass to plunder their dubloons.

By definition – remember the four freedoms – free software cannot be locked down in these ways. People can use it in any way they want (no contracts limiting use). People can distribute it in any way they want (no technical barriers to distribution). And the license actually encourages this redistribution (a fortiori, no moralistic jingoes about “piracy”, etc). At a glance, this breaks the economic model for creating and maintaining free software.

One of my heroes, Dolly Parton, has famously said about herself that “it costs a lot of money to look this cheap”. We can borrow this phrase as a slogan for the problem I’ve just described: “It costs a lot of money to be this free.” So that’s a problem that stands in need of some explanation. Given that it costs a lot of money to create free software, where is the money coming from? Who is footing the bill for WordPress?

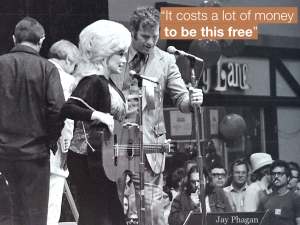

The first group that comes to mind is what I call “the hobbyists”. This is Matt Mullenweg in 2004. Matt is one of the co-founders of WordPress, and the story of WordPress’s founding is, I think, typical of the story of the hobbyist free software contributor. Matt was a user of the free blogging tool b2. He and Mike Little decided in 2003 that they wanted to fork the tool to add some more features and make it a better fit for their own use cases. And they decided that their changes would be actively made available to a larger community. They weren’t getting paid for this – it was something they did for fun, to scratch their own itch. This kind of hobbyist is effectively donating his own labor to the project. And this is part of the story of who funds projects like WordPress.

The second class of folks responsible for funding free software is the business owners who donate some of their employees’ time to the projects. This is Matt Mullenweg in 2013. By this point in the history of WordPress, Matt is a successful businessman. Through Automattic (the company that runs the commercial wordpress.com) and Audrey Capital (his venture capital firm), Matt donates large amounts of employee time to the WordPress project. And Matt is only the most notable of a growing group of businesses that are doing something similar: a number of WordPress-focused web development agencies, webhosts, and other companies are following suit. So that’s another part of the story of who’s paying for free software.

It’s worth noting that so far I’ve described two groups of people on opposite ends of a spectrum: the hobbyist who donates time to the project for pleasure, and the employee who contributes because it’s part of his job duties. What about the rest of the spectrum? Well, that’s made up largely of freelancers. Unlike the employee, it actually costs the freelancer money when she contributes to free software, in the form of time not spent on client work. And unlike the hobbyist, the freelancer spends most of her day working with WordPress, which makes her very good at WordPress, but also makes her pretty sick of WordPress. So, at the end of the day, it’s likely that the freelancer would rather do just about anything other than, say, write a patch to submit to WordPress Trac.

This is the freelancer’s dilemma: she has the skills, and probably the desire, to contribute. But there are direct disincentives – financial and otherwise – to doing so.

In a few minutes, I’ll spend some time talking about strategies for overcoming this dilemma. But first I’d like to dispose of a common excuse that the freelancer makes for not contributing: Someone Else Will Do It. And of course, this is true – WordPress is a large project, and it’s in no danger of not being maintained. But a closer look at who that “someone else” is makes it clear that the freelancer is, to some extent, shooting herself in the foot by leaving all the work up to others.

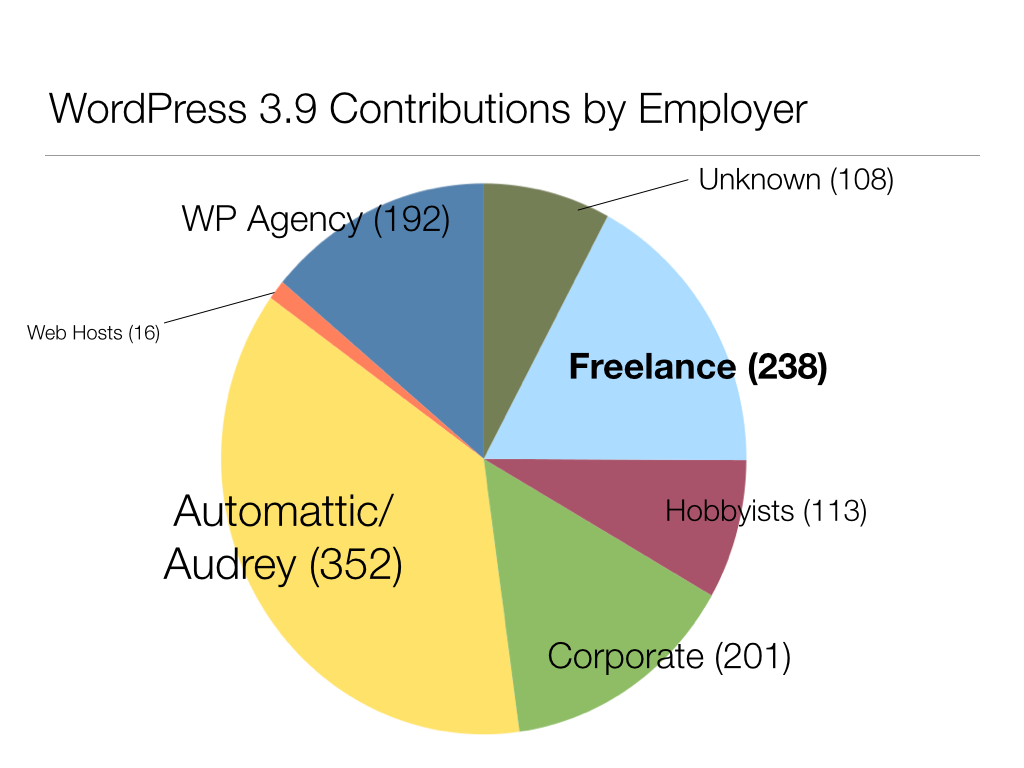

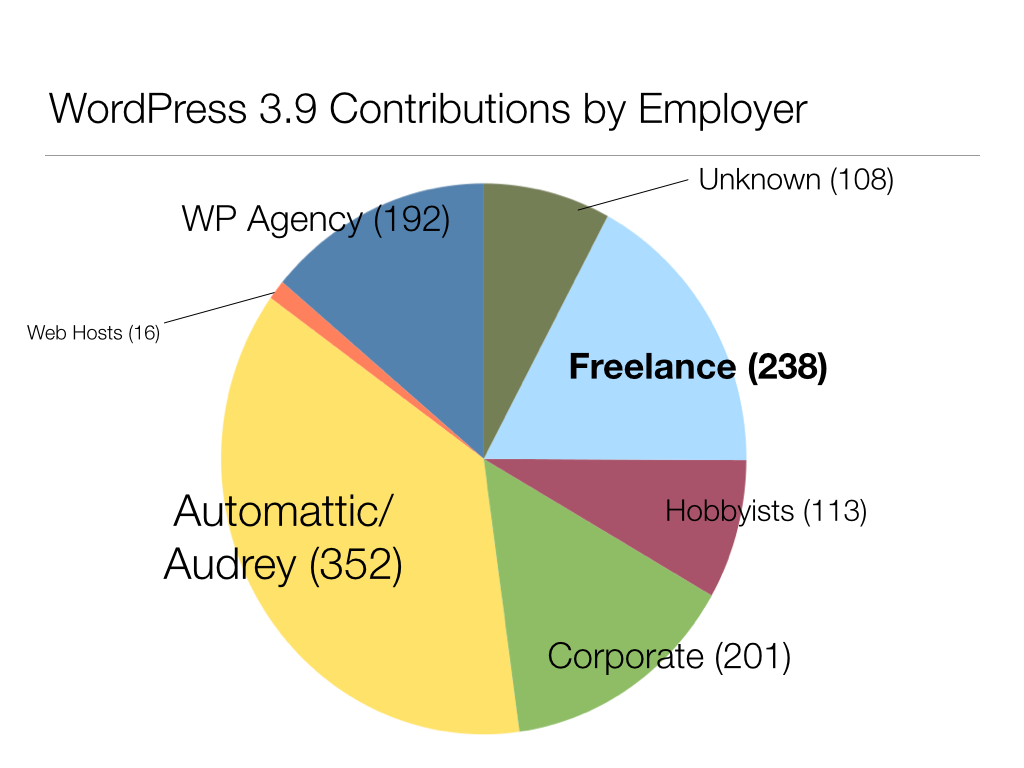

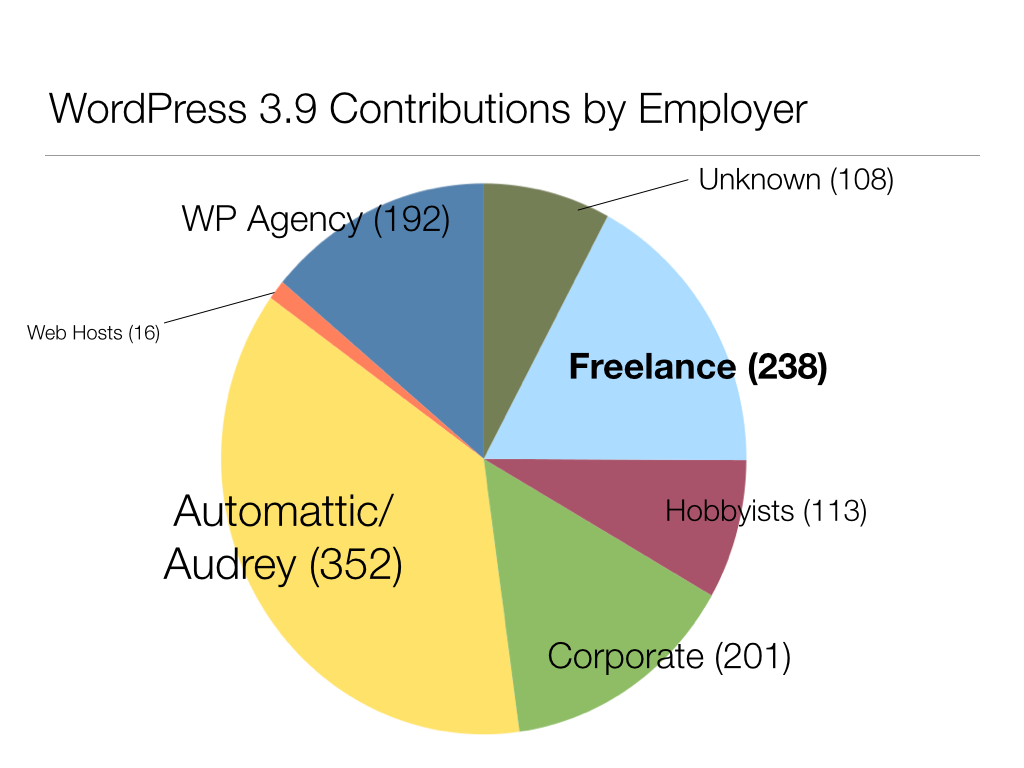

To test this, I analyzed all the changesets that made up WordPress 3.9. For each changeset, I identified the “responsible parties” – those who had received “props”, or barring that, those who had committed the patch. Once I had these counts, I researched the employment situation of each contributor, and sorted them into various employer types. [I’ll try to write up the method and results in more detail in a future post.] Now, there are many reasons why you should take this analysis with a big grain of salt. But it does gesture toward some important patterns. The freelancer represents 238 out of 1380 commits during the 3.9 cycle. And about a third of those freelancer commits belong to a single person (Sergey Biryukov).

This seems out of whack. I don’t criticize Matt Mullenweg and his generous counterparts for funding the lion’s share of this work – I commend them for it. But from the freelancer’s point of view, it’s worth taking a closer look at exactly where the largest chunks of contribution are coming from, and looking in particular at the relationship between those contributors and WordPress. Andrew Nacin is a big portion of the yellow wedge here. He spends his days working on WP core, as well as maintaining the wordpress.org infrastructure (and a handful of other very unusual WP-based sites). The folks from Automattic are focused on wordpress.com, a huge and hugely influential WordPress network, but an idiosyncratic one in a number of technical and conceptual ways. And people in larger WP agencies as well as the Corporate category are working disproportionately on fairly large, high-traffic sites, largely for big media companies. But my impression is that these sites do not really represent what makes up the bulk of the WordPress sites in the world, most of which are fairly small and low-traffic – the kinds that are typically built by freelancers. There are specific considerations that are important for building sites of any type, and the people who build sites of that type are best positioned to ensure that the WordPress software is a good tool for building those sites. If freelancers want to ensure that WP continues to be the right tool for them and for their specific use cases – and they should – then they ought to be getting involved.

So let’s talk about some concrete strategies that the freelancer can use to contribute without doing undue damage to her bottom line.

The first strategy I want to discuss is what I call “patronage”. This is Mozart. Like many musicians and other artists before him, his art was financially supported (at least in part) by rich aristocrats. This was a time when there were fewer ways to make a living from the masses (no CD stores, for example), so one of the only ways for artists to get by was to find a person with deep enough pockets to fund the art. This worked out pretty well, at least in some cases: Mozart got to write music and put a roof over his head, the patron got the prestige of the commissioned works, and posterity got the benefit of Mozart’s music.

Free software patronage works in a similar way. Here’s an example. I wrote a plugin called BuddyPress Docs for a project at the City University of New York called the CUNY Academic Commons. They wanted a way for users to edit documents collaboratively, a sort of hybrid of Google Docs and a wiki, from within BuddyPress. It was clear from the beginning that this was a tool that lots of other BuddyPress installations could use too. I was very fortunate to be working with Matt Gold at CUNY, who has a deep understanding of the broader benefits of free software. So we agreed early on that the plugin would be made available on the wordpress.org plugin repository, and that the CUNY Academic Commons would pay me for at least some of the necessary upkeep on the public plugin. In exchange, the CUNY Academic Commons gets some good publicity. They’re listed as a plugin author. The plugin has been downloaded some 78,000 times, which sounds good when they are writing reports to their funders. And since the plugin was originally written for CUNY in 2011, I’ve parlayed it into a number of other patronage arrangements, with the University of Missouri and the University of Florida each requesting custom functionality which we arranged to have rolled into the publicly available plugin.

When it works, the patronage model is perhaps the ideal way to do free software development. Remember: our original dilemma was that time spent writing free software was time not spent doing client work. But when you’re working on patronage, you’re doing both at the same time.

But it’s hard to get patronage right. First and foremost, you have to find the right client. They’ve gotta be open-minded – and, ideally, excited – about the prospect of giving away a product that they’re paying for. And in most cases, that product is going to cost them more than it would cost them if it were not intended for general use – as any plugin or theme developer knows, creating something meant to be distributed is a good deal more complex and abstract than something meant for a single client site. Certain types of clients will be more naturally amenable to this sort of thing than others. I work primarily with public universities, where it’s pretty easy to sell the idea of using public funds for work that will benefit a broader public. Your mileage may vary.

Just as important, patronage only works on the right kinds of projects. Freelance projects usually start with the client producing a monolithic list of requirements. Part of the freelancer’s art is to turn this list into a scope of work that both satisfies the client’s needs and contains discrete items that are appropriate for general release. One of your jobs as developer is to know what’s needed in the community at large, and to massage your contracts in order to extract standalone items that address these needs.

You also want to make sure that you only agree to patronage setups when you – and the client – are willing to be in it for the long haul. Releasing a plugin means that you have a certain responsibility for upkeep. Include at least some of this upkeep in your ongoing maintenance contract with the client. And make sure that you pick something that you personally will want to continue to work on down the road.

One last point to make about patronage is this: Dirty work is hard to sell to a potential patron. Everyone likes the idea of having their name attached to an exciting new plugin. Fixing arcane bugs in an upstream project isn’t nearly as sexy. Unless you’re a really smooth talker, patronage probably won’t fund more than a small portion of your free software work.

So that’s patronage. It’s great work if you can get it, but it’s hard to get it right.

A more broadly applicable strategy for freelancers is what I call “the reputation cycle”.

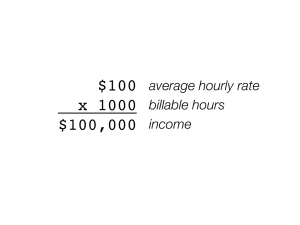

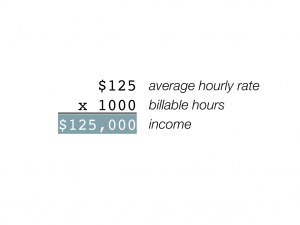

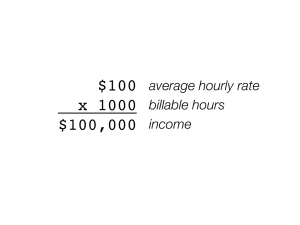

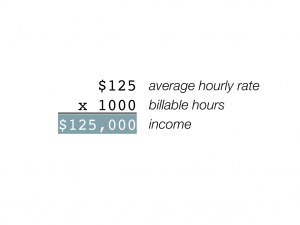

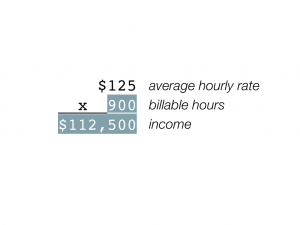

Let’s start with some arithmetic. Say you work 1000 billable hours per year, and charge an average of $100 per hour. This would give you a yearly income of $100,000. Now let’s say that one day your hourly rate went up to $125. What happens to this equation? Well, you have a few options. One is to make an extra 25 grand:

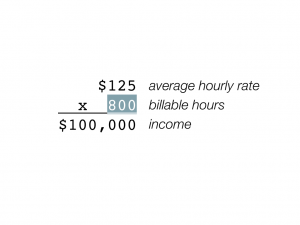

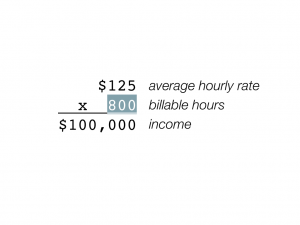

Another is to shoot for the same income, but to work less:

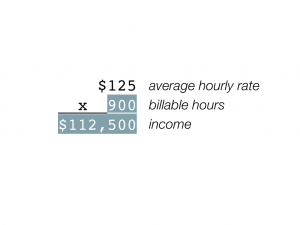

Or you can split the difference, working a bit less but making a bit more:

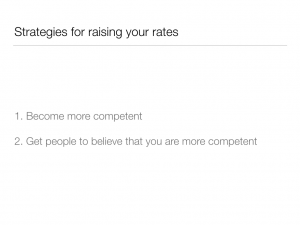

This is a fun math lesson, but now we have to go back and answer the question of how to make this happen. If you’re charging $100 per hour for client work, how do you get yourself to $125 so that you’ll be faced with the choices described above? The question of how to raise one’s rates is, of course, the Great Question of All Freelancers, and there’s much that could be said (and has been said) about it. But there are a few very simple tips that I can give for justifying higher rates: get better at what you do, and get your clients to believe that you are better at what you do.

So what does this have to do with my talk today? Well, it so happens that these two tried-and-true methods for justifying higher rates are also two of the primary benefits of contributing to free software projects:

Let’s talk about these two claims in turn. First: how does contributing to WordPress make you better at using WordPress? I’d hope that this is self-evident at least to an extent, but it’ll be helpful to say at least a few words about the specifics.

Consider code review. hen you submit a patch to WordPress, it’s usually reviewed and commented on by a number of committers, and probably multiple other seasoned contributors. How much would it cost if you had to pay for this kind of professional code review? This point is especially important for the freelancer, who, by definition, works alone. The opportunity to learn new techniques and t get high-level feedback on your work is invaluable. And this kind of feedback is a free benefit of contributing to the project.

Another way that contributing can make you better at WordPress is that it forces you to learn more about WordPress. There is simply no better way to learn about how WP works than by diving deep into its very bowels. For every ticket you decide to adopt, you’re bound to find one feature of the software you never knew about; or learn one more odd quirk; or ideally, fix one problem that was bugging you. Over time, these little things add up: you’ll find yourself choosing better client implementations, making fewer mistakes, and getting your paid work done more efficiently.

There’s a lot more that could be said about how building free software improves your skills. But let’s change course for a moment. Remember, we’re trying here to suss out how contributing to free software can justify charging higher client rates. For that to happen, the client has to believe that you’re worth those rates. So let’s talk a bit about reputation.

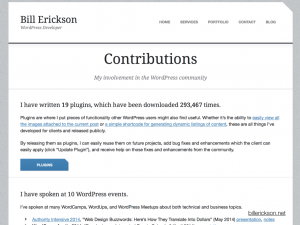

Maybe the most direct benefit from contribution is that it gives potential clients independent verification that you are, in fact, an expert in your field. Put yourself in the place of a client who wants a WordPress website but doesn’t have the technical skills to tell apart self-proclaimed “experts”. Are you willing to pay a 10% or 20% premium for someone who can prove that they’ve written a popular plugin or even written a small part of WordPress itself?

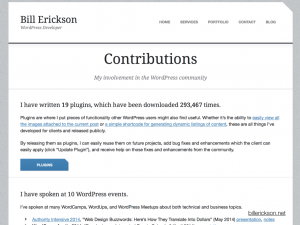

Check out this page from the website of WordPress freelancer Bill Erickson. He’s listed details about his publicly available plugins, download counts, a list of WordPress-related presentations, patches accepted to Genesis and WordPress, and so on. I’m sure Bill lists this information here because he’s proud, and rightfully so. But it plays an equally important role in verifying his claim to be a WordPress expert.

Simply blogging about WordPress is another way to demonstrate your expertise in a concrete way – an especially effective one if you write a blog post that ranks high on Google. I’ve written technical posts about BuddyPress that still get Google traffic five years later. My rate for BuddyPress consultation (which makes up almost all my client work) today is almost 10 times what it was in 2009, when I started doing this work. What justifies that in the eyes of clients? There’s a lot to be said about that, but in part, it’s things like:

Each of these is an independent verification to clients that I am, indeed, the expert I claim to be. This stuff is hard to fake.

A less obvious way in which contribution can have ramifications on reputation is that it helps you tap into a network of quality referrals. Active participation in the WordPress community will get you noticed by other members of that community. And prominent members of the community are likely being solicited with very attractive job offers. Becoming a trusted member of the community taps you into this referral network. I personally send a few dozen referrals every month, and the people I send referrals to are exclusively those I know from the WordPress and BuddyPress community.

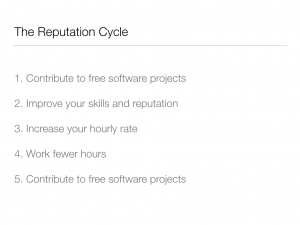

Let’s go back to the main point here. I’ve been talking about a strategy I call the Reputation Cycle. Here’s the “cycle” part of it.

When you contribute to free software, over time you will improve your skills and reputation. As a result, you’ll be able to demand higher rates from your client work. When that happens, you can work a bit less over the course of the year, and still make the same amount of money (or even more!). Some of that freed-up time can then be put back into your free software work. And the cycle begins again.

I think this is pretty compelling. But if you’re not convinced that this is a good thing for you personally, consider this: This kind of cycle is imperative for the future of WordPress and free software in general. Take another look at this chart I showed earlier:

One of the patterns it suggests is that a disproportionate part of funding for WordPress’s development comes from a fairly small number of sources: Automattic, Audrey Capital, 10up. When a freelancer spends an hour working on WordPress, it’s being paid for by the freelancer’s client (whether directly or indirectly). In this way, the freelancer converts a marginal amount of the money spent by clients on WordPress-based sites into a direct benefit for the WordPress free software project.

This is a form of redistribution. One way to think of it is that the freelancer is a kind of Robin Hood – taking from the rich to give to the poor. But I think this is a bit coarse, and prefer to think of it as a more subtle effect. Freelancers have the chance restore some equilibrium to the system, by shifting some of the onus of footing the bill for WP off of Matt Mullenweg and a few of his generous counterparts and onto a much broader subset of the WordPress universe. This dynamic ensures that the project is funded in a less centralized way, and helps to make the future of the software more secure.

One more thought to wrap things up. I’ve been freelancing full time for about four years. Over that time, I’ve used the techniques described today to get myself to a point where I spend about 50% of my working time doing non-paid free software work. I’ve chosen to orient my career this way because, like Richard Stallman, the father of the free software movement, I consider free software to be a critical tool in accomplishing some important moral and political goals that have implications beyond the software itself. But I’ve intentionally avoided framing today’s talk in this way. Nothing about how contributing is the “right” thing to do, or that you “owe” it to WordPress. If you are a freelancer who couldn’t care less about the GPL or user freedoms or Richard Stallman, my argument is that you still ought to contribute out of mere self-interest. And if you’re a freelancer who does care about these things, my argument is that there are strategies that help you to contribute without undue financial sacrifice. In my view it’s a brilliant structural feature of communities structured by the GPL that you don’t have to care about the ethical implications of free software in order to benefit from those implications. In other words, it’s equally valid to contribute for the sake of others or to contribute merely for yourself.